Desert Revival: New Evidence Shows Humans Carved Rock Art Deep in Arabia at the End of the Ice Age

In a stunning new study published in Nature Communications (Guagnin et al. 2025) researchers overturn a long-standing assumption: that the interior of northern Arabia lay completely depopulated between the Last Glacial Maximum and ~10,000 years ago. (Nature)

Water Returns, People Follow

Between ~16,000 and ~13,000 years ago, seasonal lakes (playas) began to form in the Nefud desert—probably the first surface water in the area since the parched heights of the LGM. (Nature) These ephemeral wetlands would have offered lifelines in an otherwise hostile landscape.

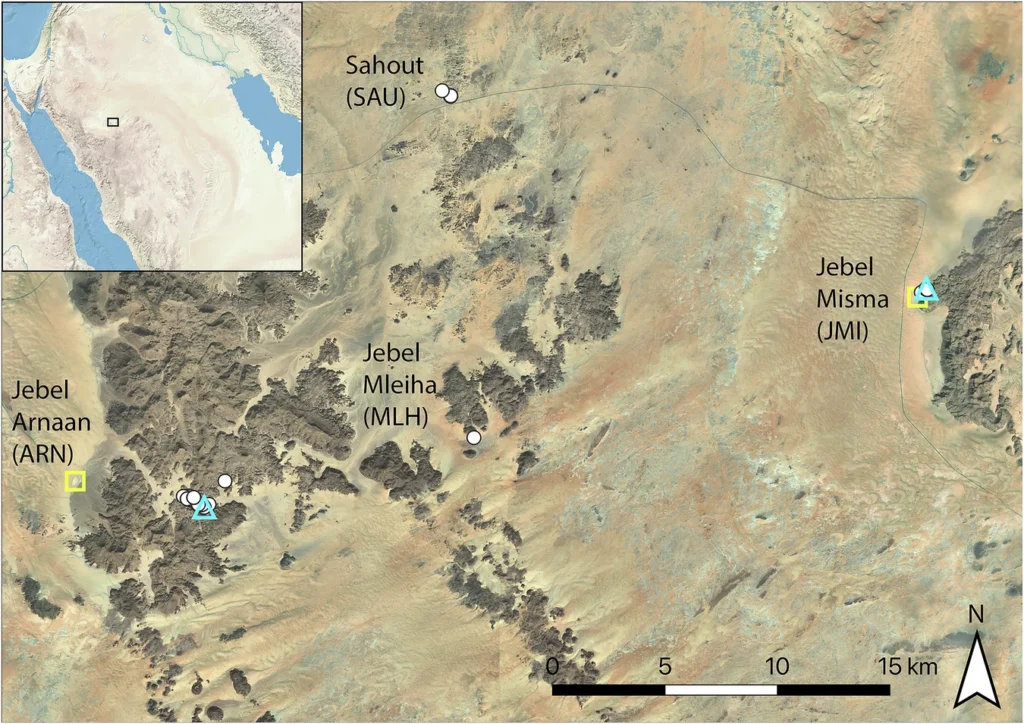

Around 12,800 to 11,400 years ago, new excavations uncovered solid archaeological evidence of human activity. Stratified deposits yielded stone tools, hearths, and engravings directly beneath rock art panels—showing that people were living in and marking these desert margins at the Pleistocene-Holocene transition. (Nature)

Monumental Rock Art as Landmark & Memory

These were not casual doodles. The team documented 176 engravings on 62 rock art panels—most life-sized animals like camels, ibex, equids, gazelles, and even a rare aurochs. (Nature) Some panels stretch 20+ meters and stand 34–39 meters up cliff faces, clearly intended to be seen from a distance. (Nature)

The researchers argue the art acted like a map in stone—markers of water, routes, memory. Engravers risked physical danger to create them, choosing positions visible across the landscape and often superimposing new images atop older ones in successive phases. (Nature)

Connections to the Levant & Cultural Networks

Interestingly, the toolkits recovered show clear links to the Levant. The team unearthed El Khiam points, Helwan bladelets, decorative beads, and pigments—items typical of Pre-Pottery Neolithic and Epipalaeolithic traditions farther north. (Nature) This suggests that Arabia’s early occupants were not isolated but part of broad networks of knowledge and movement.

Why This Changes the Story

- It pushes back the timeline for organized human presence in the Arabian interior—showing that people returned to this harsh land far earlier than previously believed.

- It casts monumental rock art not as decorative afterthoughts, but as strategic tools: marking water sources, guiding travel, anchoring cultural memory in dangerous landscapes.

- It highlights how adaptation and connectivity went hand in hand—as people pushed into tougher regions, they remained part of exchange networks spanning deserts, mountains, and oases.

This work helps reframe our picture of Late Pleistocene human resilience. Arabia was no empty wilderness waiting for people to arrive; instead, it was a dynamic frontier, navigated, engraved, remade by human agency at the very moment the Ice Age drew to a close.